The French are known for their passion – occasionally to the point of over-enthusiasm. In his latest look at the wine category for Just Drinks, commentator Chris Losh finds that, on this occasion, that tendency to exaggerate is not misplaced for the country’s wine producers.

There are times as a journalist when silence on the part of your interviewees can give you a better idea of what’s happening than a thousand words of comment. I’ve spent much of the last fortnight chasing up wineries and growers across France, to find out how they have been affected by the frosts last month, and it’s safe to say that people are not queuing up to offer their opinion.

Typically, when pursuing a bad-news story such as this, if you put out enough feelers. you’ll eventually get a reaction along the lines of “It’s bad in places and some people have been badly affected, but we escaped more or less unscathed”. This time, however, the silence has been almost ubiquitous, which can only mean one thing: It’s bad. Really bad.

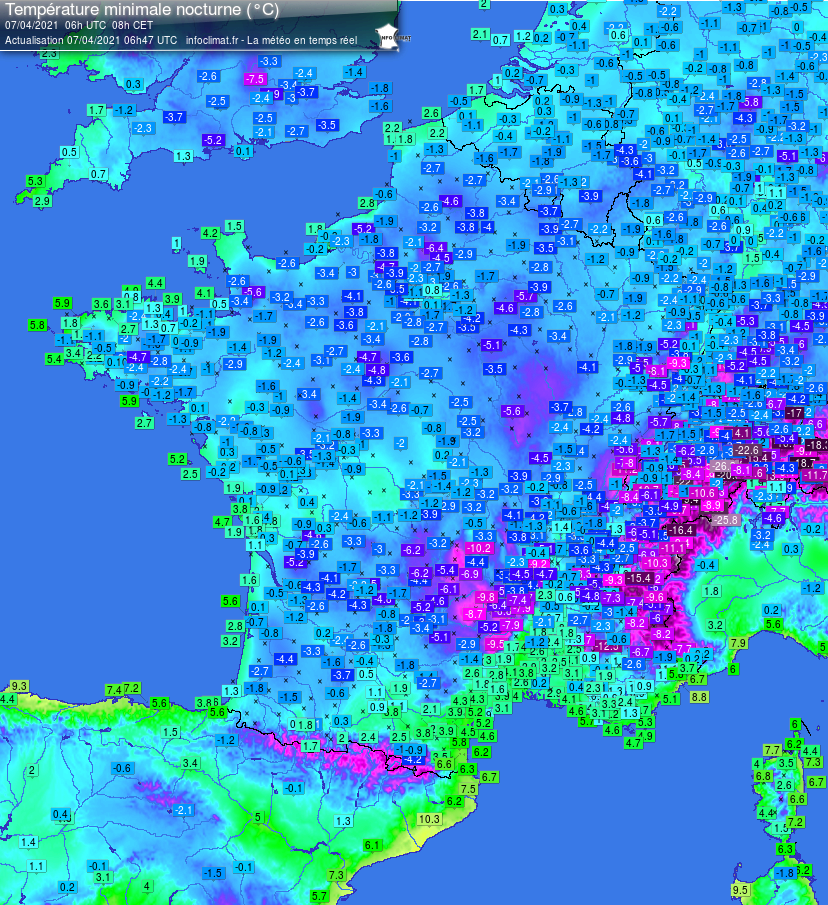

April was full of cruelly beautiful photos on social media of ‘bougies’ lighting up vineyards across France, and smoke curling across twilight slopes as winemakers lit tubs of wax and burned hay to keep frost at bay. The image that made the greatest impression on me, however, was neither of these. Rather, it came from the French meteorological website, Infoclimat. For the night of 7 April, the graphic showed almost the entire country covered in the blue markings that denote sub-zero temperatures as a blanket of Arctic air nestled over France.

Weather frost – infoclimat

From the western edges of the Loire in the west to Alsace in the east, and from Champagne down to Bordeaux and the southern Rhone, the country was – quite literally – freezing.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataFrance is no stranger to springtime frosts. But, there are four issues here that make 2021’s episode especially devastating.

Firstly, the cold snap occurred after an atypically warm February. At a time when vines should still have been huddled against the cold, sap started to rise and the growing cycle started far earlier than usual. Vines were about two weeks ahead of schedule across the country. The cold air hit smack in the middle of flowering.

Secondly, as mentioned, it was unusually far-reaching. Northern regions such as Burgundy, Champagne and the Loire are used to a degree of frost. But, it’s a once-in-a-generation occurrence for every wine region to be affected. There has been nothing comparable for the last 70 years.

Thirdly, the frost was unusually severe – -5C was commonplace, and it dropped to these levels for three nights in a row. Growers are often able to take mitigating action against temperatures a little below zero, and to trust to luck that they won’t get hit if it’s a one-night occurrence. There was no escaping three consecutive nights of such severe polar air, though. Growers who escaped the first night were captured by the end of the cold snap.

The combination of advanced vineyards and prolonged frost was a perfect meteorological and climatic storm.

But, it’s one that has been exacerbated by the fourth point: that this frost comes on the back of a particularly harsh six-year run where France has seen its production decimated repeatedly. In the six years since 2016, the country has had four vintages impacted by frost. Maybe not to the ubiquity of 2021, but still affecting over 50% of the country’s vineyards to some extent.

This is not normal. In the 15 years from 1979 to 2015, Infoclimat records just five noteworthy frost years. Or, to put it in context, France has seen more or less as many vintages hit by severe cold during the Trump presidency (ish) as through the tenures of Carter, Reagan, Bushes I and II, Clinton and Obama, combined.

Places that hardly ever see frost have seen it this year. Places that are used to a little are bracing themselves for losses of 50%. Regions that are used to it have been all but wiped out. The scale of the loss in regions such as Burgundy and the Loire is awful.

As mentioned earlier, it’s hard to get reliable figures on the damage, at present. Officially, wine regions are waiting for the frost season to finish, and to see whether secondary buds improve matters somewhat before putting numbers on the devastation.

It’s just as likely that growers and their regulating bodies are too shellshocked to speak.

So, let’s do some intelligent guesswork. Over the last ten years, France’s average vintage size has been 44m hectolitres. 2017, the last big ‘frost’ vintage was 36m hl – a drop of 20%. I’ve seen estimates in the French press putting this year’s likely crop at 32m hl – a decline of 30% – though going off some of the off-the-record feedback I’ve been amassing, it could well be lower even than this.

What’s certainly true is that it’s lop-sided. The ‘volume’ appellations of Languedoc, Roussillon and Provence may record almost normal years, while the ‘value’ regions certainly will not. The country’s wine income is going to take a kicking over the next few years.

What we can say with a fair degree of confidence is that prices are likely to rise across the board – with the possible exception of Champagne, whose policy of blocage helps mitigate against peaks and troughs in supply.

But, whether prices will be able to rise enough to make up the shortfall is highly debatable. In a COVID world, not many importers, buyers or consumers will be able to stomach double-digit price increases. Yet, how else can producers counter a 90% cut in their income? Growers in Burgundy do, at least, have the opportunity of charging good money for their wines. And, barrel ageing allows for a certain spreading out of sales to smooth over thin years. For producers of, say, Loire Sauvignon Blanc, Muscadet or Provence rosé, which are typically made and sold within six months of vintage, there is no such buffer.

For many growers, the economics of wine have been less than compelling for a while – even in a decent year. They make little sense at all in frost vintages.

I’d expect that we’ll see a number of vineyards going up for sale in the next 12 months, which might (if we’re really scratching around for positives) provide an opportunity for more financially-sound operations. But, three nights of polar air have done huge damage to France’s wine industry in the short term, and the ructions will be felt for some time yet.

Sales will go down, prices will go up and businesses will go to the wall. It’s been described as a national calamity, and, coupled as it is with the uncertainties of COVID, for once this doesn’t seem like hyperbole.